Ether 3:5 "Behold, O Lord, thou canst do this. We know that thou art able to show forth great power, which looks small unto the understanding of men."

Based on my many decades of experience all over North America, England, and Europe, as well as the many conversations with those from even more distant lands, western civilization clearly owes even more to its ancient forbears than is widely suspected today. And, given the focus of public discourse, we owe that debt for a single reason far less obvious than almost anyone might guess. And I'm not talking about the discovery of fire, or the invention of the wheel; those things blessed all mankind. I'm just talking about the west, and how it is that a single, relatively small faction of humanity came to lead the way, for better or worse, to the moon, and beyond.

For a fairly well acknowledged example of the sort of thing I'm referring to, one need only look to Emmer and Einkorn wheat. About 12 thousand years ago, they mysteriously acquired the trait of remaining glued to the stalk, and protected in their hulls, until harvested. This not only allowed agriculture, it practically forced it upon us. And agriculture practically imposed specialization in human endeavors, domestication of both plants and animals, and the resulting agricultural revolution. All these things, it is generally agreed, became the foundation of what we think of today as civilization: Structured, even stratified societies living in relatively close quarters for mutual benefit, plumbing, housing, transportation, and education. And, while the argument is undeniably valid that some within civilization benefit more than others, it's also pretty clear that the alternatives were, and still are, far less appealing to all its affected members. And the proof of this is simply that civilization succeeded where anything and everything else failed. (Here we are, after all.) And there are even still some examples of those eclipsed, also-ran, alternative societies extant. But they can hardly be compared (pretty much proving my point), let alone even called civilization, possessing fire, it's true, but lacking even agriculture in any tenable form.

But I said that there was a far less obvious reason than the evolution or invention (it's still debated, and relates to my duality argument) of farmable wheat. So what might that be?

The alphabet.

The earliest writing that we know of so far dates to about 8,000 years ago. Where it arose is still debated. New discoveries are forever pushing back the date, and relocating the point of origin. But the principle appears to have been a big hit, and it caught on like wildfire, quickly turning up in China, Europe, Mesopotamia, India, and Egypt. But the writing systems we've deciphered were syllabic, reflecting the agglutinative nature of the languages they represented. (And, by the way, even English is an agglutinative language, which is why you so often see words defined by their syllables, and even hyphenated at their syllabic breaks.) And syllabic writing systems automatically preclude the advantages we're looking for here simply because no obvious method for organizing them offers itself.

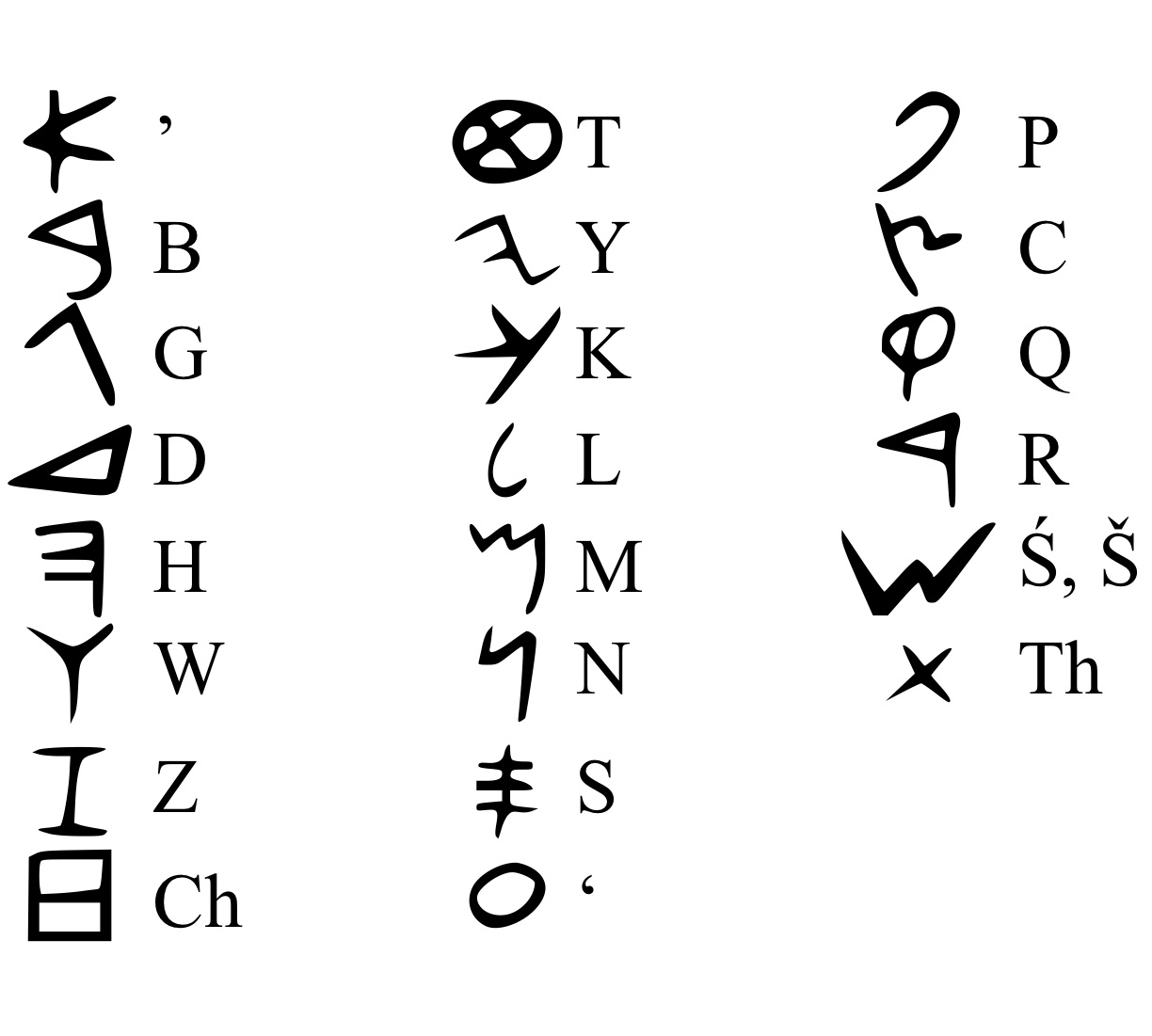

It wasn't until about 4,000 years ago, fairly recently in this writing craze, that the Proto-Sinaitic (ancient Hebrew) script would be born, eventually becoming the Phoenicians' 'phonetic' alphabet. This may have developed as a lowest-common-denominator method of learning and teaching the many languages encountered as seafaring began to broaden trade networks, but this step alone was a huge revolution in language, and comparable to agriculture in its impact.

How so?

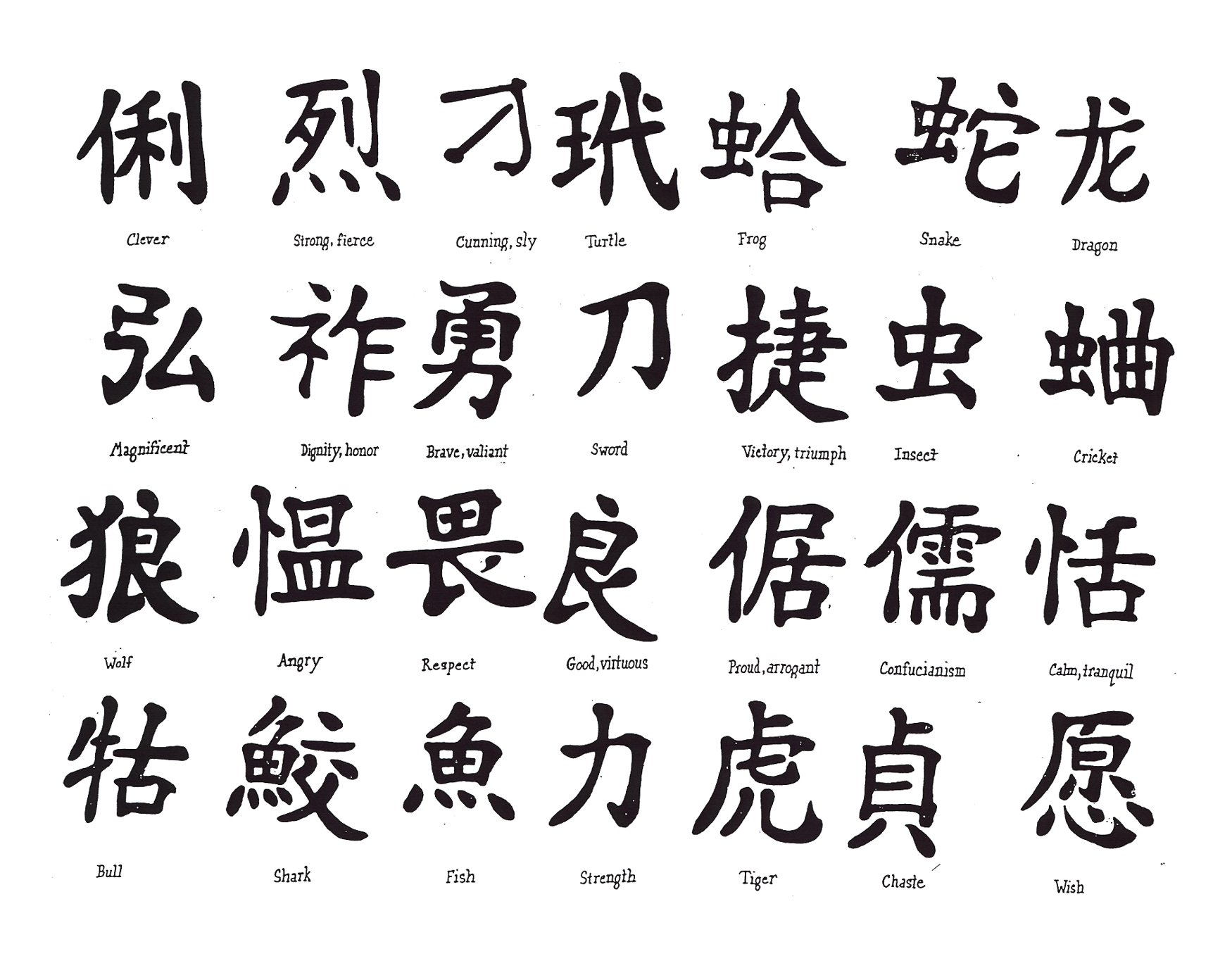

Because sub-dividing words, which had recently begun compounding into fairly unwieldy, polysyllabic monstrosities, into smaller sounds even than their monosyllabic origins, and representing those sounds with graphic symbols, made it possible, for the first time, to be able to read, pronounce, perhaps even understand a word never before seen or heard by a reader. Had one encountered a new word when reading in any previous system, its meaning could simply not be guessed. One had to be taught the pronunciation and meaning of every symbol by another who had also been taught, in order to understand what was written. This is exactly why the ancient Egyptian languages remained unintelligible to us for so long: All those who could have taught us the meanings of the symbols were dead and gone, and there was no dictionary to turn to. Indeed, Champollion was only able to make his breakthrough because the Rosetta stone provided a sort of dictionary. And it's for precisely these reasons that Chinese and Japanese children today must expend so much mental capacity memorizing thousands of symbols just to attain basic literacy. So useful and successful is our Roman alphabet, that China has long offered official, Romanized versions of their proper nouns for western use, even using it to teach their children their own language.

But the alphabet itself was only the first step down this road. It needed to be followed to its logical conclusion. And, although practically integral to its name, the second step, alphabetization, did not evolve simultaneously with the alphabet, making it something of a retronym. That is to say that we didn't call the alphabet the alphabet until after alphabetization was invented, and that's because the name, alphabet, comes from the fact that the order of the first two letters, alpha and beta, became a standard. No one thought to record what we used to call our list of letters, or whether it even had a name at all back then. And that's part of the proof that this little miracle was already being taken for granted from the start. Still, or perhaps because of that, it would take about another thousand years for an order of our letters, the alphabet, to become standard.

And recognizing that is why standards organizations were created. Advances today simply can't wait a couple of thousand years before they gain broad acceptance. And that was yet another, tangential result of our alphabet.

The third step, numbering those letters, came pretty soon after alphabetization. Assigning ordinal numbers to the letters of the alphabet not only enforced their now standard order, it also lent to the substitution of numbers with letters. This was rather awkwardly applied in Roman numerals, but who hasn't seen lists indexed with a., b., c., ...? Lettering is now a standard feature of every western word-processor's bullet-point feature. The adoption of the Indian/Arabic decimal system quickly sidestepped the Roman numeral impediment, but, by then, checksums had become the established means for error-checking copied texts. Accurately copied texts quickly led to libraries, lots of libraries. And anyone who had learned the phonetic alphabet, and alphabetization could find any scroll or book in the library, and start reading it. If they encountered a new word, they could almost certainly pronounce it, and, in doing so, perhaps even recognize it, perhaps even guess fairly accurately at its meaning. And, if even that wasn't enough, they could then turn to the alphabetically-organized dictionary for help.

Contrast all this with, say, Akkadian, Sumerian, Nesite, Egyptian, Chinese, or Japanese. These writing systems were, and still are, so mentally rigorous, they gave rise to a whole, new, professional class: The Scribes. Worse, they required entirely different, and not entirely adequate, methods for storing and retrieving information. We know this because we've found their libraries, and we know how they organized them, and it wasn't pretty. In most cases, the closest thing to an organizational method they had was by subject, which is actually still used in libraries today, but in addition to the loosely alphabetically-based Dewey Decimal System. Chinese dictionaries are sorted from simpler symbols to more complex ones, based on the number of strokes in the character. But, obviously, even a single stroke can take many forms, so, as with subject, this method will only get you to the right neighborhood, not the right house, or even the right street. You'll likely have to do a lot of searching past that point to get to what you're searching for. And that takes more than just mental prowess; It takes time. And time, as we all know, is money, or, for our purposes here, societal progress.

Is it any wonder the Chinese are now using the Roman alphabet to learn Chinese?

Westerners, meanwhile, have been raised in a simpler, more intuitive tradition that freed up more mind power for other tasks. (You can see where I'm headed with this, right?) The less arduous western writing system, along with its concomitant methods of ordering and numbering, engendered in western minds what is known in the field of computer science today as a hashing algorithm. We all learned this so long ago that we've completely taken it for granted. Surely no one would ever think to add to their résumé that they've mastered the skill of hashing, or even alphabetization, but, clearly, if you think about it, you'd hardly be able to perform the simplest functions at your job without this skill. Most everything we do employs them. Certainly we have tools now to automate these things, such as the sorting feature in our spreadsheet applications, but just ask yourself why this feature is even available. It's there to be able to arrange the information into a familiar order where you can more quickly find and assess it.

How did alphabetization accomplish this? Reading a list is reading a list, right?

Not always. And this relates to my defense of vertical menus and tabulated information: No one reads everything; It takes too much time and effort. You need it ordered, sorted, so you know what to skip without losing anything critical.

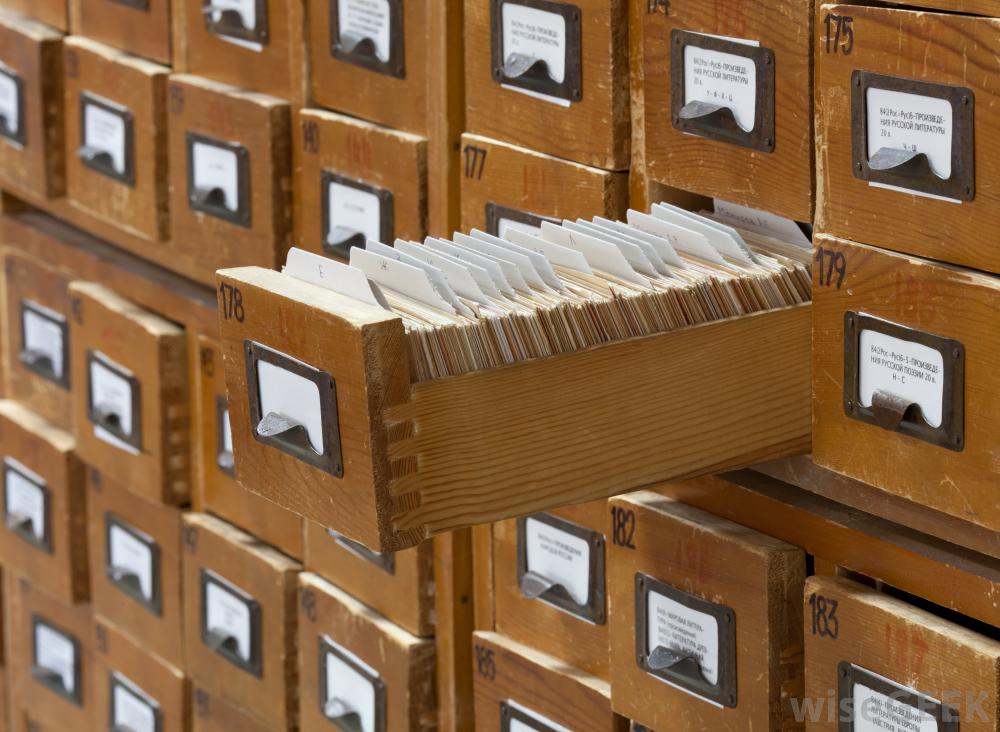

Recall your school library's card catalog. Recall also that, knowing alphabetization, you knew that the letter, M, falls right in the middle of the alphabet. And, given this, when entering the library looking for a book by Marcus Aurelius, or a book on Mathematics, you knew to head straight for the middle of the cabinet, because that's where the M drawer would be. What you did NOT need to do was start reading at the drawer labeled, A, and keep reading past drawers, B, C, D, E, etc., until you arrived at M. You just walked right past all the others, and likely straight to the one you needed, based on the physical dimensions of the cabinet, your familiarity with the alphabet, and your mental, spacial-orientation skills.

THAT ... is a hashing algorithm. And THAT makes information access 2 or 3 orders of magnitude faster than previous systems, such as that used in Ashurbanipal's library. That is what made for things like The Library of Alexandria, and all her daughters ever since.

Likewise, any warehouse worker knows his bin locations (a form of organization deeply tied to alphabetization) by heart. So, when gathering the items on his pick-list, he, more often than not, walks straight to the very location containing the item needed to fulfill the order.

That, too, is a hashing algorithm, and both are the culmination of that oh-so insignificant choice, made so long ago, by ancestors who could hardly have imagined what heights their decisions would propel their descendants to. And this hashing method is the very foundation of the best databases today, whether libraries or warehouses. Mind you, it's not so much the alphabet, or even alphabetization, but the easy, mental, spacial orientation those tools foster which has made our ability to structure, store, and retrieve information and material so consistently, so intuitively, and so easily accomplished that, literally, not only can a child do it, children do do it. We all do it, and we do it so regularly, and so unappreciatively, that we don't even know that we're doing it at all anymore. It's just the way things are done. It's the way things have always been done. And no scribes are required.

It's the very definition of a paradigm.

And, so, as computers began to evolve from other, existing technologies (a hard disk, for example, is a blend of old phonograph and magnetic tape technologies), it never even occurred to us to build them around any other system than the one at the very core of western civilization: Alphabetization, Decimals, Checksums, and the Hashing that we'd already been using for millennia.

Case in point: ASCII. That's the numbering of the characters I mentioned earlier, and what gives us our modern iteration of the checksums invented by ancient, Hebrew scholars. (See: MD5 sums)

Just as a mutation in wheat, eons ago, led to a split in humanity between the hunter-gatherers and the farmers, so, too, did a simple variance in writing systems send humanity down two, widely divergent paths, only one of which would bring electrical networks, radio communications, digital electronics, personal computers, and the very web you're reading this on right now. The other, it is my contention, whose users are universally acknowledged, and even praised by western observers, as intellectually superior, unwittingly put themselves at a disadvantage, and into the role of the hare vis-à-vis our tortoise by burdening themselves with the mentally crippling handicap of an unnecessarily complex writing system, making alphabetization, and all the developments which flowed from it, literally unthinkable.